St. Jerome, the Vulgate, and Our Biblical Heritage

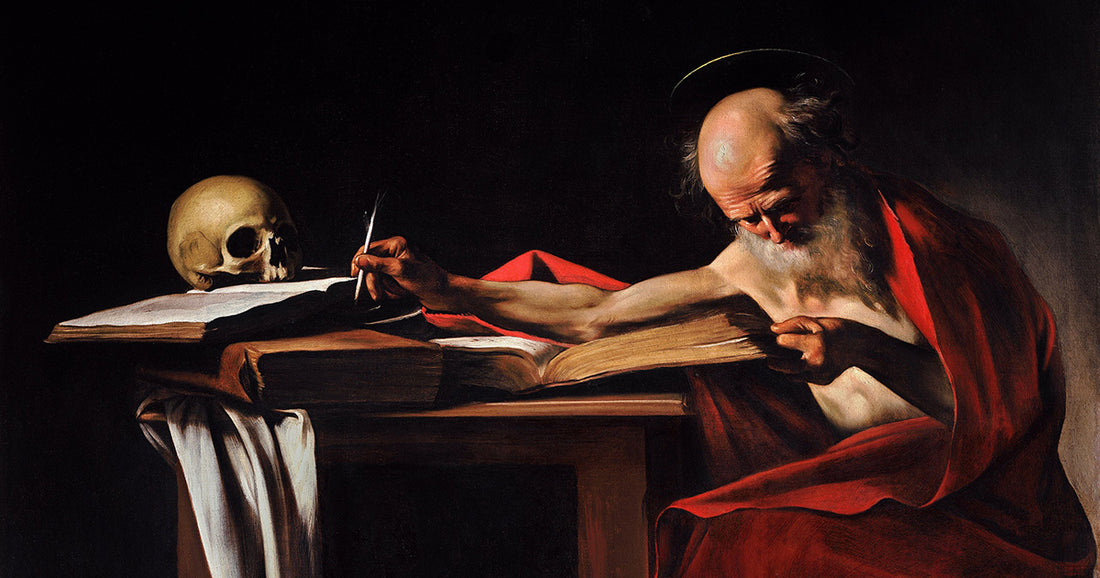

Matt DunnCaution: This post refers to Vulgate material.

An Inheritance to Treasure

On September 30, we celebrate the feast of St. Jerome, Church Father and translator of Scripture. Writing to a friend, he once bantered “Lynxes, they say, when they look behind them, forget what they have just seen, and lose all thought of what their eyes have ceased to behold.” Living only in the moment ignores both the past from which we can learn and the future in which we can apply that learning.

Unlike Jerome’s lynx, let us look to the past as a guidepost to the future. As a Church Father, Jerome is our ancestor in faith. Family traditions passed down through generations are some of the most precious inheritances a younger generation can receive. Understanding our grandparents and great-grandparents: their identities, where they came from, and why, not only gives us insights into ourselves but reveals stories we can pass on to the next generation.

This should also apply to the Scriptures. In order to more clearly understand the readings we hear at Mass or read with our family at home in our native language, it helps to know our Bible’s family tree as well. No Catholic look at our scriptural ancestry would be complete without looking at what has been promulgated officially, according to the Holy See, as the “typical” edition of the Bible for Latin Rite Catholics, “to be used especially in the sacred Liturgy but also as suitable for other things.” I refer to the Latin Vulgate Bible.

Assembling a Canon

The Vulgate, and what the phrase “Vulgate Bible” means, has evolved over the years (more on that later), so let us begin even prior to its existence and go through our biblical family tree starting as far back as we can. Alfred Durand gave us many insights into the origin of the New Testament. The first written texts of what became the New Testament were probably the epistles, sent by Paul to various churches around twenty to thirty years after the Resurrection (Durand mentioned the possibility of the original non-Greek text of Matthew’s Gospel predating this, but most scholars favor the concept of the epistles’ having been written first). What happened when these churches received these letters? While the letters may have addressed issues specific to their audience, the recipients, not surprisingly, desired share-and-exchange information. So the church in Rome would receive a letter from St. Paul, and exchange copies with, say, Galatia, so they could all have an understanding of the teachings being handed down. This is suggested by many scholars, including George Reid, who writes that Corinth was the first church to assemble a complete catalog of Paul’s letters.

If the Gospels were written after the epistles, when were they recognized as canonical? Early Church Fathers, writing at the end of the first century, date them as having been not just written, but publicly released and widely known between A.D. 50 and A.D. 100. It is also obvious from these writings that, even at this early date, though other writings existed, the four Gospels we know today were already seen as authoritative. There is even evidence of them already having been used as part of early Masses: St. Justin Martyr, in the first half of the second century, wrote: “For the apostles, in the memoirs composed by them, which are called Gospels, have thus delivered unto us what was enjoined upon them … And on the day called Sunday, all who live in cities or in the country gather together to one place, and the memoirs of the apostles or the writings of the prophets are read.”

Around this time, the first concept of a “Vulgate” Bible came around. But this term refers not to the Vulgate Bible as we know it; it was primarily a response to a need. Since the books’ manuscripts had come from various languages (Reid, for example, quotes a bishop named Papias referring to the original Manuscript of Matthew being written in Aramaic, but the earliest circulated versions were in Greek, the language of the educated at the time. Of course, many Old Testament works had been written in Hebrew and translated as well). While Greek may still have remained the language of the elite, by the middle of the second century A.D., the Roman Empire had spread such that the more common language was Latin. So translations of these already translated documents began to appear in the “common” language of Latin. The Latin word for “common” is “vulgate.” Often times these translations are known as the “Old Vulgate,” or Vestus Latina. Unlike Jerome’s Vulgate, which we will explore shortly, this was not a standard “edition” of the Bible, but the phrase refers to the many different translations into Latin across the Roman Empire, based in part on the Septuagint (The Greek Translation of the Old Testament from Hebrew). These translations existed as far back as around A.D. 150.

The next generations of our biblical family tree, Reid describes as a “Period of Discussion.” During this period, other non-Gospel writings were evaluated to determine their canonicity. Fathers such as Eusibius, Origen, and Cyprian, had traveled widely, allowing them to evaluate writings various local churches had collected, examining their history and authenticity. Healthy debate and the guidance of the Holy Spirit brought up the cases for and against individual works as being part of the Canon.

Jerome and the Vulgate

By the late fourth century, the Church had completed the work of identifying which works composed the Canon of Scripture. However the problem of various editions remained. Pope Damasus, understanding the concerns of differing sources, wished to correct this by having a “common” translation. To assist in this he called upon St. Jerome, who had shown his expertise in matters of exegesis and languages at a recent synod. This was not expected to be as large of a project as it eventually became: Damasus asked Jerome to revise the Old Vulgate only for four Gospels. Jerome began this process in A.D. 382, and was able to complete it in about two years, using many original Greek manuscripts, and comparing these to the Old Vulgate versions that existed.

Upon completion of this, Jerome then continued embarking on a translation of the psalms—from the Greek Septuagint—but later began again, focused more on the original Hebrew than Greek. Eventually, he completed many other books of the Bible, as well as overseeing or influencing what would eventually become the most well known Latin Translation, a common Vulgate edition—completed around A.D. 400—which despite not (yet) having official recognition, became the standard for versions of the Bible for over a thousand years.

In 1546, the Council of Trent finally gave the Vulgate official approval. Contrary to popular belief, the Vulgate was not then (nor ever) declared to be the official Bible of the Church. In fact, Trent only stated the council “declares, that the said old and vulgate edition, which, by the lengthened usage of so many ages, has been approved of in the Church, be, in public lectures, disputations, sermons and expositions, held as authentic; and that no one is to dare, or presume to reject it under any pretext whatever.” In other words, the Vulgate was approved. No one was to assume it was not approved. But it did not exclude the possibilities of other editions.

The Vulgate’s Legacy

It’s position as the Gold Standard for Bibles lasted another 400 years. The Gutenberg Bible was a Vulgate. Many classic English translations (such as the Wycliffe Bible, the Douay–Rheims, the Confraternity Bible, and the Knox Bible), all were translated from the Vulgate. Cardinal Gasquet notes that in 1907 Pope Pius X initiated a commission to have Benedictine monks prepare a critical edition as a precursor to an effort to revise the Vulgate (the article link above fascinatingly describes the process of how involved it was to print the pages for revision in a relatively modern but still pre-word processing era). This revision was officially begun by Pius XI in 1933, but was not completed, for reasons we will touch on shortly. The Vulgate’s time as the standard for all translations ended with Pius XII’s encyclical Divina Afflante Spiritu in 1943. This encyclical mandated that future translations be made from the original languages, rather than the Vulgate.

Despite this, even Divina Afflante Spiritu noted the importance of the Vulgate, so the deliberate revision begun by his predecessor continued for decades. After the Second Vatican Council, the psalms and New Testament were retranslated into Latin for use in the Mass. This, combined with most of the Old Testament completed by the Benedictine monks begun by Pius X, comprised the Nova Vulgata, the current translation approved by the Vatican for all Latin liturgical rites. Current vernacular Mass translations still primarily use the Vulgate.

Most Catholics have never seen or read from Vetus Latina, Jerome’s Vulgate, or Vulgata, and most probably never will. Yet the effect that these versions have had on every Catholic’s life is undeniable. It is like the skeleton around which the body of our faith is built. Even if we never see it, it is always there supporting us.